Money As Equity: For An "Accounting View" Of Money

the

issuing states, and are reported as a component of public debt under

their respective national accounting statistics (ESA, 2010). Similarly,

banknotes issued by central banks, and by extension central bank

reserves (which represent the largest share of money base in every

contemporary economy), are considered as liabilities of the issuing

central banks and are accounted for as central bank debt to their

holders.

By Biagio Bossone e Massimo Costa

In

fact, even though the law says that money is “debt”, a correct

application of the general principles of accounting does raise deep

doubts about such a conception of money. Debt typically involves an

obligation between lender and borrower as contracting parties. We wonder

which obligation may fall upon the state from the rights entertained by

the holders of coins, or which obligation may fall upon the central

bank from the rights entertained by the holders of banknotes or by the

banks holding reserves.

We specifically

refer to these three “species” of money because they are all “legal

tender”, that is, in force of a legal power, they absolve their issuers

of any responsibility to convert them into other forms of value. This is

not the case, obviously, for monies that are convertible on demand into

commodities or liabilities issued by third parties (e.g., currencies of

other countries). On the other hand, conversion of reserves into

banknotes does not constitute a central bank’s debt obligation, since it

only gives rise to a substitution of one form of liability for another

that is issued by the same central bank and is not redeemable in any

other form of value produced by third parties.

A similar question

can be asked with respect to the money issued by commercial banks in the

form of sight deposits, inasmuch as this money plays a similar role to

that of legal tender in almost all bank-customer relations (excluding

interbank obligations, which require central bank money as settlement

asset).[1]

We shall return to this type of money later on in the article. Below we

focus on legal tender monies issued by the state or the central bank.

Legal tender: if it is not debt, what else is it?

In the old days,

local sovereigns guaranteed that the coins they issued contained a

specific amount of precious metal (silver or gold).[2]

Still in those days, banknotes gave their holders the right to claim

for their conversion into silver or gold coins. To be able to match

those claims, sovereigns needed to hold adequate volumes of metal

reserves. The same kind of obligation committed central banks with

respect to their reserve liabilities issued to commercial banks.

Therefore, all three species of money gave origin to true debt

obligations that were legally binding on their issuers and could be

triggered on demand by their holders at any point in time.

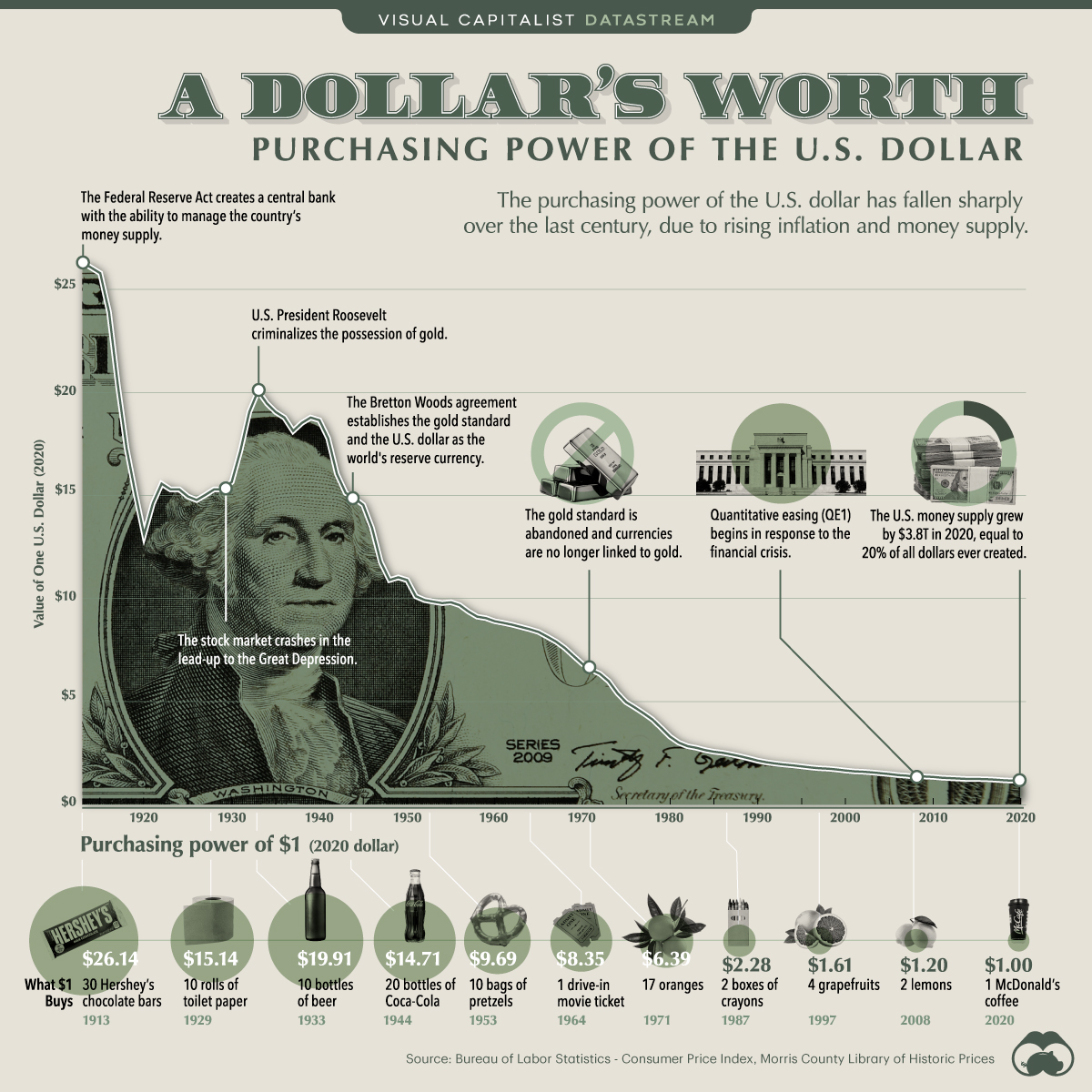

But

this was the past. Today, convertibility has all but disappeared for

each of the three money species under discussion. Coins have lost most

of their relevance and have been largely replaced by paper money.

Convertibility of banknotes has been suspended long ago, and the

abandonment of the gold-exchange standard, about half a century ago,

marked the definitive demise of “debt” banknotes even at the

international level. Finally, the reserve deposits held by commercial

banks and national treasuries at central banks are today delinked from

any conversion obligation into commodities or third-party liabilities

(except where the central bank adheres to fixed exchange rate

arrangements, the economy is dollarized, or the country is under a

currency board regime).

Therefore, although

for legacy reasons, or simply due to conventional choice, money is

still allocated as debt in public finance statistics and central bank

financial statements, it is not debt in the sense of carrying

obligations that imply creditor rights.[3] Rather, it represents equity for the issuer and, as such, it implies ownership rights.

The “Accounting View” of money